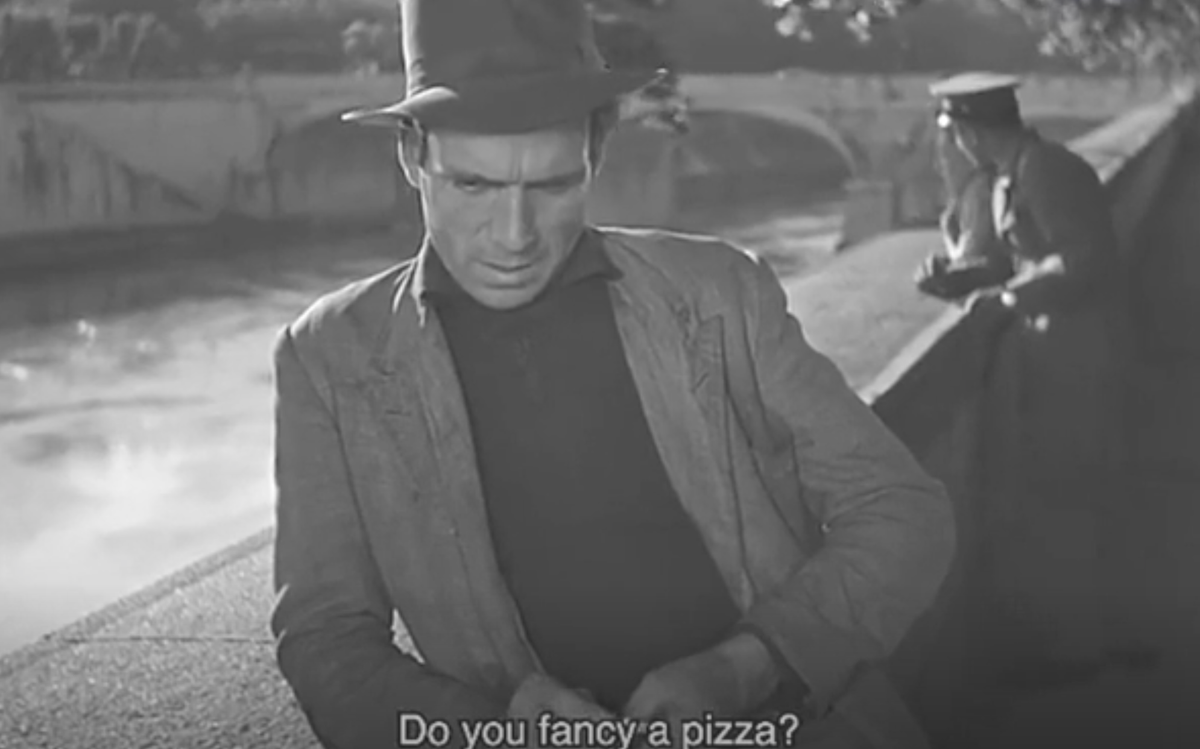

do you fancy a pizza?

(Note: Kind of a long-ish one today. Sorry.)

I've struggled with how to write about film for indoor animal. Movies are not easy to write about. There's a lot to them: production value, cast, themes, writing quality, entertainment value, cultural significance, etc. Even if you touch on all the important things, there's a chance a reader hasn't seen the one you mention, which is annoying. But it's even worse if they plain don't like the movie. I'm not trying to convince anyone of anything here. I mean, everyone has different tastes, but am I being subjective or objective when I discuss a film?

It's into this minefield that I now stumble. And I take the risk because I love movies. Always have. Especially in the theater. When I went to college, I learned I could get a certificate in Film Studies (a major was not offered at the time I was at my college), so I did. It was there that I was exposed to an overwhelming number of new films and styles. We went through the eras, studied some of the classics, dabbled in foreign film. I have fond memories of many discussions from those days. More than a few of the films broke my heart, broke me open, and changed how I thought about the world.

My main takeaway from that program was something one of my professors told us François Truffaut, the director and one of the founders of French New Wave, said. I've never located the exact quote, but he said something along these lines: when the film ends and the lights come on in the dark theater, it's best to go to a café and finish the conversation the film started. If you walk out, and you don't care to discuss it, the movie probably had nothing to say.

This is why I want to talk about films. They matter. So, I'll try.

But first, a digression:

Just under a decade ago (I think) I was waiting for the Hudson-Bergen light rail in Hoboken. It was a pleasant day, but something was on my mind. (I can't for the life of me remember what it was all these years later – which means it likely didn't matter.) The train was a few minutes away, so I paced in circles around the platform and worried the Rosary in my pocket. I'd estimate that I was 90 to 95% in my head, and 5 to 10% aware of the world through which I was moving. And then I went deeper into my head. So deep that I lost track of my body completely.

I snapped back to the there and then as I realized that my next step was out over a chasm. There was no solid ground to catch my foot. My mind rushed to make sense of what was happening, to find a way to correct this mishap. But it was too late. I had stepped off of the platform and out into the nothingness above the tracks.

Thankfully, the tracks were only 3 feet or so beneath the platform. They are not six feet down (or more) like the PATH station a few blocks away or the subways in Manhattan. Still, my momentum carried me into the void and my leg buckled under the weight of my body when my foot finally hit the concrete below. I tried to catch myself, but just ended up scraping up both hands. I was lucky I avoided crashing into the metal rails or against the concrete edge and even luckier I didn't hit my head on anything. Flat on the ground, I assessed the damage. Bumps and bruises, but no broken bones, no concussion.

It clicked in my brain that the train was coming. I became certain that I only had moments left to live. Before I could lift my head, I imagined looking up to see the light rail car bearing down on me. I thought I had to make a split-second choice: hurry up and out or lie flat and hope for the best. My head snapped up and my eyes fell on... nothing. The light rail was still one minute away. I had time to escape.

I climbed back onto the platform and dusted myself off. I glanced around. No one was nearby, but there were a handful of people further off. They didn't look at me. I thought it was to spare me embarrassment, but maybe they hadn't seen. I felt strange. Embarrassed, sure, but it wasn't just that. Something had happened, but nothing was changed. The light rail car rumbled up and opened its doors. I got on as if nothing happened. The day became normal again.

I think I've only told one person in my life this story. I didn't even tell the person I saw on the other end of that light-rail journey. It's not a flattering story, but it's not a terribly unflattering one either. It's kind of a non-story. But I think about it every so often as some event, or non-event, that happened to me in the past. On days when I am living inside of my head, it pops into my brain that this may be my fate if I don't come back to the real world. The brain can be a cage, and we all need a reprieve every so often. Which brings me to my favorite headline of all time from The Onion:

Deeper in the satirical article, it mentions that though the man says, "I'll be out soon! Can you just wait?" he really means, "I am real. I am present. I exist. Please, you have to understand. I am real. See me. Just see that I exist."

Asserting one's own existence can take many shapes, but the desire to do so often comes from an internal – conscious, or unconscious – existential crisis. These crises can take place in a bathroom in Kennebunk, Maine, on a light-rail platform in Hoboken, New Jersey, or in post-World War II Rome. They can be comedic, strange, or both utterly grim and wildly profound. I think the first time I witnessed an existential crisis (and had the mind to know what was going on) was in the 1948 Italian neorealist film Bicycle Thieves* (Dir. Vittorio De Sica). (Here it is available online to watch for free if you are interested!)

I'll do my best to quickly set the scene: an Italian family man with two young children finally lands a job posting advertising bills around town based on the sole fact that he owns a bike. But there's a catch: he pawned his bike. His wife takes the poor family's prized possession, bed sheets, and goes to the pawn broker. In exchange for the sheets, he gets his bike. Then, he goes to work. However, while up on a ladder doing his job, a young man comes along and steals his bike. Without it, he can't do his job. Without his job, his family won't survive. He brings along his eldest son, a boy of 8 or so, and they search all over town for the missing bike. The actor, Enzo Staiola, who plays the son Bruno is enchanting on screen:

The journey gets more heartbreaking as their efforts reap no rewards. The driving force behind the second act – a man trying to find his bike – is so simple, yet so effective, and executed so well. It's a subtraction-driven plot, whereas most movies continually add things and grow. The stakes are laid out perfectly: his life and his family's lives will cease if he cannot work and he cannot work without his bike. These reasons, and more, are why people are still talking about this film 75 years later.

But it isn't all all-caps grim. In the middle of this adventure, when things look their darkest, the father has an idea: he's going to take the son to get some pizza. He says:

What the hell... We might as well go out in style... What's the point of worrying about it at all?

The son's face lights up. He's ecstatic because now he's out on the town with his father. For him, the horrible day has taken a 180 as they walk into a crowded restaurant, one full of people and music. They order food and it comes. Bruno digs in:

This moment breaks up the dramatic momentum that has been building and building by showing a moment of fleeting joy in otherwise challenging lives. Even when life is at its worst, there can be warmth, music, communion. Without this scene, I don't think the film would've become a classic. Many modern movies focus too much on plot and lack an integral moment like this (in my opinion) – and it's the audience that suffer.

But back to Bicycle Thieves. Despite the reprieve in the restaurant, the father can't leave his conundrum behind. He turns inward again. After the food's been eaten, he shares what's going on in his head with his son: the bike's gone forever.

Later, father and son stroll by a soccer match as it ends. Fans pour into the streets and many of them grab their bikes and ride off. It's maddening: the haves and the have-nots. The father, taunted by the number of bikes he sees, turns further inward, becomes almost deranged. He looks away, and sees a lone bike in an alley. No one guards it. He gives his son money to take the trolley home and says he'll meet him there. The son rushes to catch the trolley, but fans overcrowd it and he can't get on. The father paces around the bike, checking if there anyone's around, and swipes it. As he rides off, the bike's owner sees him and gives chase. Bystanders start to help the bike owner and a crowd chases the father. He can't pedal fast enough. They catch him and rip him from the bike. A mob of people surround him.

And Bruno witnesses the whole thing. He runs to his father and pushes through the crowd. He cries, not wanting his father to be arrested, or worse. The bike's owner doesn't press charges, but the damage to Bruno and the father has already been done: the father knows, and the son knows, that the father is just another bicycle thief, like the man they've been chasing all film.

The strength of the story comes from the thought experiment it presents: if someone steals your livelihood, your bike, will you steal someone else's and effectively put them in the same situation you are desperately trying to escape? So simple, so crushing. My college brain couldn't handle it. My eyes were opening. I was learning that life challenges each of us in myriad ways. We all suffer before we shuffle off this mortal coil. This is the rub that comes with existing.

On that day in Hoboken, something pained me and I chose to retreat inward. Had I thought about the mistakes of the man in Bicycle Thieves, maybe I could've found a better way of asserting my existence – of shouting "someone's in here!" – instead of sinking into myself. Wouldn't it have been better if I had just called someone and asked, "Do you fancy a pizza?" They might have needed a reprieve as much as I did.

Opening shot/Closing shot

Lastly, I think when it comes to writing about film, I'll do something like this to end each post. Here are the first and last shot of Bicycle Thieves. Comparing these two images can show the scope of the narrative journey, so I do this with many movies I watch. I think this film uses these visuals well. Here, we begin on a bright morning, where a crowd of men wait in the hot sun to hear if they have work. The man on the steps calls out "Ricci," plucking our protagonist out of the crowd. At the end, dusk swallows the story's participants as they disappear into a crowd.

* The film was originally translated as The Bicycle Thief and only later became Bicycle Thieves. The first title asks, "Who is the bicycle thief?" The second states it immediately. Both titles work for me.

indoor animal is curated by a human: Tim Papciak. On Mondays, he shares one link to one music video to help spark creativity in himself and in other creative types. On Thursdays, he recommends a book, movie, show, art piece, or link to some dusty corner of the internet that he believes either 1.) adds to the human experience, or 2.) serves as a coping mechanism in the year 2025. Note: this is not, and never will be, self-help content.